We gratefully thank Albert Mayr and KronoScope. Journal for the Study of Time for the permission to republish this text originally published in KronoScope, 9.1-2, 2009, p. 111-119.

The process out if which the self arises is a social process

which implies interaction of individuals in the group...

It implies also certain co-operative activities in which the

different members of the group are involved.

It implies, further, that out of this process then may

in turn develop a more elaborate organization than

that out of which the self has arisen ....

G. H. Mead (1943, p. 164)

Abstract: Interactions happen in time. Most of us will agree, therefore, that interactions benefit from an appropriate temporal structure. And for many activities there exists a more or less stringent set of rules regarding that structure. This article, on the other hand, describes how such a structure for an everyday activity, i.e. a group conversation, may arise not from the application of pre-established rules, but from a collective creative effort. The elements of this co-operative process are individual preferences regarding the principal temporal parameters, the tools are the basic procedures used in musical composition for structuring time.

Keywords: temporal interaction and co-operation, time design, temporal parameters, speech/silence.

Introduction

Time, as a specific field of interest, has made it rather late into the social sciences, where, after some years of relative prominence, it seems to have lost again some of it attractiveness. Likewise, time is not, to my knowledge, very present in the social sculpture discourse.

The Round-Table aims at letting a social time sculpture [1] unfold starting from an everyday situation: a group of persons making use of verbal, but also non-verbal, utterances and of silences in order to communicate or to avoid communication, to fight, co-operate, or simply to fill time in a more or less pleasant way. For various occasions and undertakings based on that kind of (non)-activity – such as academic and political meetings and religious services – there exist procedures and rituals – some very ancient, some new – for organizing the temporal structure of the utterances and silences. But with the exception of religious rituals – now less widely used than in the past – the primary function of the procedures is that of increasing the functionality of these encounters, while little attention is paid to bring forth aesthetic quality.

Here is where Time Design comes in. In ways similar to the different fields of visual design, Time Design proposes to combine – and make interact – formal and functional criteria in structuring the times of human activities. In this respect Time Design differs substantially from time management with its efficiency-oriented approach. Some may think that structuring a group conversation is not among the most urgent problems connected to the use of time in everyday life; but the workshop is deliberately based on a familiar situation in order to elaborate models that then may be transferred to other areas: family life, working environment, etc.

In particular The Round-table gives the participants the opportunity

- of recognizing and expressing their preferences in the temporal structuring of a group activity;

- of passing from the latent or overt acting out of temporal conflicts to a co-operative use of time;

- of employing their creative potential in the interactive process.

The Round-table also emphasizes the aesthetic qualities of group time through the use of procedures based on the parameters employed in structuring time in musical composition: duration, succession, frequency, sound-to-silence ratio, superposition.

The content of the workshop consists in the participants’ descriptions of their daily experiences with time, the conflictual as well as the gratifying ones. The descriptions themselves are not commented upon or discussed; they are instead considered only as the material for more and more elaborate “vocal gestures.” It is on these, and specifically on their temporal qualities, that the workshop focuses. “The vocal gesture... has an importance which no other gesture has. We cannot see ourselves when our face assumes a certain expression. If we hear ourselves speak we are more apt to pay attention” (Mead 1934, p. 65). In addition, more than other stimuli, collectively listened to sound creates a common time. Thus the importance of direct acoustic communication for interaction and co-operation.

How does The Round-Table function?

The workshop is structured as follows [2]:

We begin with a version in which we adopt the standard procedures for such occasions: each participant is allotted the same amount of time for his/her statement, say one minute. The order of succession of the statements follows either the sitting order of the participants or the alphabetical order of their names. These conventional procedures are completely neutral with regard to individual preferences. No indications are given as to the sound-to-silence ratio in the statements: each participant can fill or leave empty as much of the allocated time as he/she wishes without being interrupted by the others.

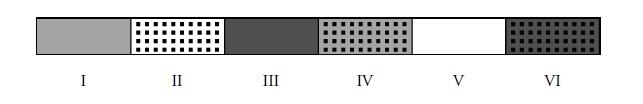

A simple graphic score illustrates this round (e.g. with six participants)

and we perform it with the workshop leader or one of the participants giving the cues for the beginning and ending of each statement.

After performing this version (and after all the following ones) we have a brief and informal exchange of impressions and ideas on some questions such as:

- How did each participant like the position he/she found himself/herself in during this first round?

- Did he/she feel the duration allocated was appropriate, or too long, too short for what he/she wanted to say?

- How was the overall sound-to-silence ratio, how were the individual ones?

- Did any of the participants feel like combining his/her statement with the one of another participant?

In the second version we work on the parameter of succession: each participant chooses the temporal position for his/her statement. The other parameters remain the same as before. We draw the score and perform it.

Questions for the exchange of impressions:

- Why were the positions selected?

- How satisfied was each participant with the position he/she had chosen?

- Has the conversation improved from a formal viewpoint?

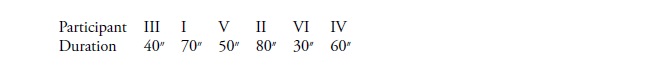

In the third version we add the parameter of duration: if the initial standard duration was 1 minute and there are six participants, a repertoire of durations, e.g. 30’, 40’, 50’, 60’, 70’, and 80’ are given to the participants to choose from together with their position in the succession. (The sound-to-silence ratio is still ad libitum). This may result in a structure such as the following:

Questions:

- How much at ease was each participant with the duration he/she had chosen? How did the choice of a short or long duration affect his /her statement?

- Was there some sense of hierarchy conveyed by the different durations?

Here we can start introducing procedures that give the temporal structure of the conversation a more distinct form. Before the individual choices are made the durations can, for instance, be arranged in ascending order – which, in musical terms, would result in a ritardando – or in descending order – which would give an accelerando; in an accelerando-ritardando ( 80’ - 60’ - 40’ - 30’ - 50’ - 70’) or in a ritardando-accelerando (30’ - 50’ - 70’ - 80’ - 60’ - 40’).

Questions:

- Was the formal character of the conversation appreciated?

- How did it affect the statements?

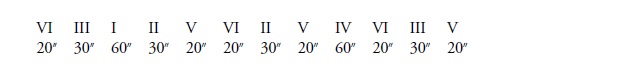

A variation in the use of the parameter duration is possible through combining it with the parameter frequency. As a basis we use the previous standard duration of 1 minute, but participants have now the option between:

- making 1 statement of 60’ as before;

- making 2 shorter statements of 30’;

- making 3 even shorter statements of 20’.

The short statements are distributed along the total duration of the version, according to the respective choices of the participants. This therefore affects also the parameter succession and we may obtain a structure such as this one:

Questions:

- Were the participants satisfied with the choice(s) they had made?

Up until now we had not addressed the parameter sound-to-silence ratio; it was left open to the participants to handle it the way they preferred. In fact, every participant could fill or leave empty as much of the allocated time span as he/she wanted. Now instead we structure this parameter. The procedure for choosing the position in the series remains the same and for the moment we revert to the previous standard duration.

There are, of course, many ways of articulating a statement in terms of speech versus silence. In order to maintain a systematic approach, four symmetric “models” of distributing sound and silence are proposed to the participants.

The duration of the statement is divided in two equal parts, with the first part devoted to speech and the second to silence – or reversely.

Model a)

Model b). The reverse of Model a).

The duration is divided in four parts, with the first and the fourth part devoted to silence, the second and third part to speech – or reversely.

Model c)

Model d). The reverse of Model c).

Participants will be asked to choose, next to their position in the series, the sound-to-silence model they want to adopt for their statement.

Questions:

- Was the “silence on command” experienced as pleasant or unpleasant? Did memories come up about situations in which one could not choose to be silent for a while?

- What effect did the structured introduction of this new parameter have on the formal result of the version?

(It is obvious that a version performed with the models illustrated above will have an overall sound-to-silence ratio of 1:1 which is the easiest to handle and appreciate for beginners. On a higher level of expertise one can opt for different overall sound-to-silence ratios, such as 2:1 or 1:2, and adapt the models accordingly).

So far all the statements have been monologues. Nobody was allowed to interfere with the speech – or silence – of another participant. Now we introduce the parameter superposition. It means that two or more participants share the same time span. (The term superposition is not to be taken literally, as the sharing of the same time span may also result in a polite dialogue; but the two or more participants in the same time span may also interrupt each other and/or talk simultaneously.)

We begin with dialogues (i.e. two persons per time span). The total duration is divided in half the amount of time spans as there are participants, for instance with six participants we have 3 time spans (in the case of an odd number of participants the resulting value is rounded up to the next integer, and one participant will be involved twice).

For the sake of simplicity we revert, for the moment, to a free sound-to-silence ratio. The durations of the time spans are equal. The choice of the position in the series now implies also the choice of a partner; this can be handled freely: Either two participants decide to be together in a given time span, or the choices of position are made individually and the “couples” are formed en route.

A possible structure of the version can look like this:

Questions:

- How did the participants experience the “filling” of a time span together with another person? Did co-operation or antagonism prevail?

- What was the effect on the overall outcome?

The dialogues then may be followed by trialogues, tetralogues…

At this point we have completed the work on the individual parameters. The following steps consist in variations and combinations of the previous versions.

Some examples:

1. Parameters: succession and sound-to-silence ratio (standard durations); I choose for you, you choose for me

The procedures are the same as before but here each participant chooses the position in the series and the sound-to-silence ratio model for another participant.

2. Parameters: succession, superposition, duration

Here we create a crescendo in density combined with an accelerando:

3. Parameters: succession, frequency, modulation of the sound-to-silence ratio, standard durations

Here two participants get to speak once, two participants twice, and two participants three times. However the sound-to-silence ratio is inversely proportional to frequency, passing from 3:1 (for the participants who speak once) i.e. 45’ speech / 15’ silence , to 2:1 (for the participants who speak twice) i.e. 40’ speech / 20’ silence, to 1:1 (for the participants who speak three times) i.e. 30’ speech / 30’ silence.

The silent part may be put either at the beginning or at the ending of the respective statement.

Once the participants have become familiar with the various techniques and have learned to appreciate the interdependence of form and content, they should be encouraged to create versions of their own.

As a final step we create a large-scale collective composition in which all the techniques are employed. Depending on the degree to which participants have shown that they are mastering the techniques a certain freedom in their use is allowed.

Discussion

The Round-Table has been practiced and performed in a variety of contexts and situations: academic gatherings (among them the ISST-conference 2001), art galleries, workshops with union officials, in centers for persons with light mental and/or psychological handicaps, as a radio program for Austria’s “Kunstradio”, and has proved to be a versatile instrument for letting temporal interactions happen.

Depending on the context different aspects were in the foreground. Most academics and artists enjoyed the challenge of having to combine (temporal) form and content, but some felt ill at ease with having to cast their profound reflections in a “straight jacket”; for the union persons it came as sort of a surprise that one can make informative statements in a brief time; for the persons in the centers it appeared to be an important experience that their times were respected and that a collectively agreed upon silence could create a link between them.

Some points that came up regarding the individual parameters:

The reflection on the parameter of succession, i.e. the question whether to make a statement before or after the other ones, at the beginning or at the end of the round or in the middle, brings the participants in touch with the more general issue of the temporal locus of activities.

In many it triggers thoughts about their behavior in everyday life and, sometimes, childhood memories (“I always wanted to be the first one.” “I feel more comfortable in the middle.”)

Duration: associations with one’s temporal behavior in daily life come up readily (“I want to get things over with quickly.” “I need to take my time.”) The exercise leads the participants also to consider whether such forms of behavior correspond to their real preferences.

Combining different durations: In present day civilization time is predominantly “formless” as we focus exclusively on its quantitative side. Already such a simple strategy for structuring time makes the participants aware that by working on the formal aspect of the activity also the functional one is improved.

Frequency: the participants agree to have their activity chopped up in pieces. This sometimes triggers memories of situations in which this happened (multitasking) and of how they coped with it.

Sound-to-silence ratio: today it is becoming more and more difficult – also because of the influence of the media with their sound-to-silence ratio of 1 to nothing – to have one’s silence respected in a group. Social hierarchies appear clearly in this respect: In our democratic societies everybody is allowed to speak, but only the silence of the powerful is considered important. For many participants it is therefore a new experience that their silence is as important a contribution to the conversation as the words they may say.

Superposition: sharing the responsibility of consciously structuring a time span – even a very short one – with another person can result in an increased awareness of one’s strategies of interaction in general.

Conclusion

Attempts at improving the organization of time in our society often fail because the persons involved are unable of articulating the reasons why a particular kind of organization is experienced as unsatisfactory, although the experience itself may be strong and pervasive. At the same time, persons often have great difficulties in expressing clearly their own temporal needs and preferences. As I have tried to show, the task of devising the temporal structure for a group conversation offers several opportunities in this direction.

In the words of Heinz Zimmermann conversations may serve as “propaedeutics to a social art to come, an art which, as an art of time, shapes human relations” (Zimmermann 1991, p. 92, tr. and italics mine).

References

Mead, G. H., Mind, Self and Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1934.

Zimmermann, H., Sprechen, Zuhören, Verstehen in Erkenntnis- und Entscheidungsprozessen. Stuttgart: Verlag Freies Geistesleben, 1991.