Let us start by looking into the rapid development of the new natural sciences of the living in the 1850s and 1860s. These disciplines, which had their roots in medicine and natural history, were indeed to become, from the 1870s, the basis for the development of psychology and, in a more indirect way, economy and sociology. As a matter of fact, in the first decades of the second half of the 19th century, rhythm was of increasing concern in these new sciences, both as operating concept and subject of investigation. Since these sciences promoted empiricist and experimental methods and rejected any idealist or metaphysical presupposition, it might have been expected that they would bring radically new insights into rhythmology by breaking with the abstract poetic metrics and the Idealist philosophy which had dominated the previous period (see vol. 2, chap 6). But this is not exactly what happened. Instead, although physiology brought about some noticeable rhythmological results, broadly speaking, it rather reinforced the Platonic metric paradigm (see vol. 1, chap. 1, 2 and 3) . This first chapter will try to trace the main reasons for this paradoxical outcome.

From Medical to Physiological Rhythm (Vierordt – 1855-1871)

To enter our subject, we may well start with Karl von Vierordt (1819-1884) who, along with Brücke and Helmholtz whose contributions I will address below, was born around 1820. As all of his colleagues involved in the development of the new experimental physiology, Vierordt was educated as a medical doctor. He thus began his research career by studying breath in the 1840. Eventually, his interest shifted to blood circulation: in 1854, he created a device he called a “Sphygmograph,” which was rapidly used in different countries to record on paper the variation of blood pressure—Marey improved it in France a few years later—and became instrumental in the semantic shift of the rhythm concept from alternation and ratio to beat and wave in medicine and physiology (see vol. 2, chap. 2). Thanks to his new device, he was able to run new experiments and publish in 1855 a full treatise on arterial pulse: Die Lehre vom Arterienpuls in gesunden und kranken Zuständen – The Theory of the Arterial Pulse in Healthy and Sick States. In 1861, he wrote a very successful textbook entitled Grundriss der Physiologie des Menschen – Outline of Man’s Physiology which was republished five times (last ed. 1877).

In the first chapter of The Theory of the Arterial Pulse (1855), Vierordt recapitulated the main previous medical contributions on the subject. He recalled the work of “Josef Struth” in the 16th century (1540 – see vol. 2, p. 18 sq. – he mentioned the 1555 ed.). Since he was directly quoting Struthius, rhythm was here clearly and very traditionally synonymous with succession of expansion and contraction of the artery of proportionate durations (see vol. 2, p. 18-25).

If we now address one of the next problems of pulse semiotics, we must admit at once that the important relation between the durations of the expansion and contraction of the artery cannot be perceived [...] by touch. This is what our Struth admits when he says: “Rhythmi non noscentur, nisi integra tempora distentionis et contractionis noscantur. – Quod vero ignota sint integra tempora motus utriusque; inde constat, quoniam et motus distensionis et contractionis integer, nobis cognitus esse non potest.” (The Theory of the Arterial Pulse, 1855, p. 2, my trans.)

Vierordt alluded next to François-Nicolas Marquet’s Nouvelle méthode pour connaître le pouls (1744 – see vol. 2, p. 38 sq. – he mentioned the 1769 ed.) which he acknowledged as a legitimate attempt at “expressing the pulse in notes of music” while calling it a “naive doctrine.” Rhythm seemed then to refer to the new musical meaning based on the regular succession of beats and bars which developed during the 18th century.

Later medicine was not entirely poor [on that matter], though it has failed to set up clear symbols for the rhythm of the pulse [Rhythmik des Pulses] allegedly observed through the sense of touch, in order to sharpen the description of the pulse. That’s why a physician in Nancy, Marquet [...] tried to express the pulse in notes of music. [...] Numerous engraved music examples served as an explanation of this naive doctrine. (The Theory of the Arterial Pulse, 1855, p. 18, my trans.)

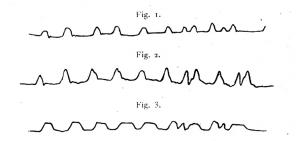

But a few pages below, Vierordt used again the term “Rhythmik,” seemingly referring, this time, to the succession of beats and waves as it was recorded with the Sphygmograph he had just invented in 1854. As a matter of fact, Vierordt provided a large number of figures representing records of pulse waves (similar to those taken in Marey’s, Kries’ and Ewart’s books provided in vol. 2, chap. 2).

It sometimes happens that the artery evades the platelet; here, the best way is to compress the artery slightly below the observation point of the pulse; the rhythm of the latter [die Rhythmik des letzteren] is not disturbed by this. (The Theory of the Arterial Pulse, 1855, p. 33-34, my trans.)

Noticeably, these three acceptations of the term rhythm were almost exceptions in his book, either because they belonged to the past or contrarily, for the last one, to a much too modern conception. Most of the time, Vierordt used rhythm as regular alternation or as mere succession of alternate movements, regular or not. He considered, for instance, the binary movement of respiration as much rhythmic as the heart motion.

The reason why the systole and diastole of the ventricles last approximately the same time in humans, however, is still an unsolved problem of the theory of heart movements [...]. The answer to this last question, on which my attempt stumbled, remains unsettled, and I can, at the most, draw attention to analogous processes of rhythmic movements in muscles during animal action. In frequent respiration, the duration of inspiration and expiration is approximately the same; the muscles of inspiration rest about the same time as they are in action; the same applies to the exhalers. When acting, the muscles show similar rhythmic alternation between work and rest. (The Theory of the Arterial Pulse, 1855, p. 70, my trans., same use p. 123)

The rhythm of respiration is thus here an arbitrary one; in order to make the effects of respiration more pronounced, it is also possible to purposely take a deep breath. I have followed this method in my experiments on this question. One uses a suitable lever device for recording the respiratory movements on the kymograph. (The Theory of the Arterial Pulse, 1855, p. 190, my trans.)

If we turn now to his very famous Grundriss der Physiologie des Menschen – Outline of Man’s Physiology (published in 1861 but I will use the fourth revised and expanded edition published in 1871), it is worth noticing, to begin with, that Vierordt never used the term rhythm for the periodic development of the embryo. I could not find a single occurrence in the whole section dedicated to embryology (p. 604-658). This is one more piece of evidence showing that there was no “rhythm episteme” in the 19th century (for this dubitable thesis see Wellmann, 2010) and, moreover, that rhythm was not a concept used by the new developmental physiology of the time, at least until the 1900s (for a discussion of this contention, see vol. 2, chap. 5).

In his Physiology, Vierordt used instead the term rhythm mainly in three ways. The first referred to a strictly regular succession of phenomena, as the beating of a clock—actually, in this particular instance, of the regular meeting of two slightly desynchronized clocks. This use appeared—but only once—in the section dedicated to hearing.

A sound that hits both organs of hearing, albeit unequally, is simply heard. But the fusion of the sensations of both organs has its limits; one gets, for example, different impressions as one hears two clocks of slightly different beating speed with one or both ears (E. H. W e b e r). In the first case, one distinguishes the periods where the beats of both clocks meet, and considers them as a repetitive rhythm. If, on the other hand, a clock is held in front of each ear, one is able to decide which one beats faster but not to [recognize] any of the rhythms [aber jener Rhythmus fehlt]. (Outline of Man’s Physiology, 1871, p. 334, my trans.)

The second use equated rhythm with a series of cycles or a periodic recurring. This use was naturally prevalent in the section dedicated to “Periodische Körperzustände – Periodic Body States” (p. 591-604). It also appeared in the section concerning the contractions of childbirth (p. 571) or to describe the flow of blood in arteries (p. 141).

A closer examination of the course of the normal functions may lead to observe the constancy of certain cycles, including multi-day cycles. The very phenomena of the three-day, four-day, and above all of the very rare, seven-day pathological rhythm, and the strange multipla of the latter, to which menstrual cycles belong, all point to this. [But] this subject, as well as the previous attempts to demonstrate multi-day rhythms in normal life in various functions, cannot be discussed here. (Outline of Man’s Physiology, 1871, p. 600, my trans.)

Most of the time, though, Vierordt used rhythm, in a rather traditional way in medicine, as synonymous with alternation of two contrary movements of various durations, whether by some body muscles under nervous stimulus (p. 74, 83, 95), the heart (p. 123, 124, 125, 127, 129, 145, 209), the arteries (p. 138), the respiration (p. 145, 202, 497, 579), the brains skins (p. 491), or the contractions of childbirth (p. 521). A full section of the chapter on “Blood Circulation” (chap. VII) was dedicated to the “Rhythmic of the Systole and the Diastole” (§ 128, p. 119) and another one in the chapter on “Respiration and Perspiration” (chap. X) to the “Rhythmic of Respiratory Movements” (§ 212, p. 202-203). One particularly illustrative example will suffice here.

When respiratory gas exchange is maintained to a sufficient degree by periodic injection of air into the trachea, a curarized animal, whose nervi vagi have been cut out, shows an alternate rise and fall [ein abwechselndes Steigen und Sinken] in the arterial blood pressure, as a result of a periodic increase and decrease in the activity of the vascular muscles [in Folge einer periodischen Zu- und Abnahme der Thätigkeit der Gefässmuskeln]. The stimulus to this rhythmic movement probably originates from alternating states of the medulla oblongata, as respiratory center. (Outline of Man’s Physiology, 1871, p. 209, my trans.)

To put it in a nutshell, Vierordt’s physiological studies in the 1850s and 1870s tended to enlarge the application of the various notions of rhythm derived from medicine but they did not change its Platonic metric frame.

From Medical to Physiological Rhythm (Wundt – 1864)

The second important figure we have to deal with is that of Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920). Wundt was a bit younger than Vierordt. In 1855, he majored at the University of Heidelberg in medicine, but doctoring was not Wundt’s vocation and he turned instead to physiology, which he studied for a semester under Johannes Müller—the “father of experimental physiology”—at Berlin. In 1856, at the age of 24, Wundt took his doctorate in medicine at Heidelberg, but habilitated as a Dozent in physiology. Two years later, he became an assistant to Hermann von Helmholtz, position in which he remained until 1865, with responsibility for teaching the laboratory course in physiology. His first research resulted in the Lehrbuch der Physiologie des Menschen – Textbook of Human Physiology published in 1864-1865 (Kim, 2016).

In this Textbook, Wundt often used the term rhythm, as it was customary in his time in medicine and physiology, to refer to the alternation of the diastole and systole the successive durations of which were in a certain ratio (p. 295, 297, 318, 321, 332, 335).

Donders imitated the rhythm of the heart sounds perceived by the stethoscope by movements of the hand and let these movements register on a rotating cylinder. (Textbook of Human Physiology, 1864-1865, p. 295, my trans.)

As Vierordt, he used it also, on the same semantic basis, to refer to the alternation of respiratory movements.

1. Rhythm of respiratory movements. The movements of the breath consist of rhythmic changes in the space of the chest cavity, which are caused by the successive contraction and relaxation of certain muscles. (Textbook of Human Physiology, 1864-1865, p. 355, also p. 392, 393, 394, my trans.)

As its cardiac counterpart, the rhythm of respiration explicitly implied a ratio between inspiration and expiration which yet could voluntarily vary.

The rhythm of the breath is a very regular one. The inspiration is shorter than the expiration, according to Vierordt, in the ratio of 10:14–24. Inspiration transforms directly into expiration. But on the other hand, before any new inspiration, there is a pause that is 1/5 – 1/3 of the total duration of one respiration. (Textbook of Human Physiology, 1864-1865, p. 356, also p. 374, my trans.)

For that very reason, as Vierordt, the young Wundt still clearly distinguished rhythm from beat or pulsation.

With a very significant increase in pressure, however, the number of cardiac pulsations [Herzpulse] may decrease again, while at the same time the regular rhythm [regelmässige Rhythmus] of the latter is usually disturbed (Heidenhain). (Textbook of Human Physiology, 1864-1865, p. 318, my trans.)

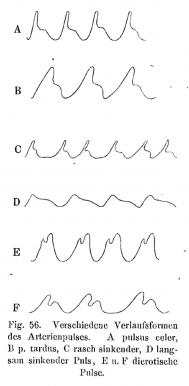

Unsurprisingly, the “pulse” was increasingly described as “pulse wave – Pulswelle” or “pulse curve – Pulscurve” and represented through figures taken from the latest studies run with Vierordt’s and Marey’s sphygmograph (as in fig. 56, p. 311, reproduced here above). It was also measured by it frequency, i.e. the number of recurring beats by time unit. For example, in the chapter dedicated to “The Blood and the Blood Movement,” Wundt often spoke of “pulse frequency – Pulsfrequenz” (p. 322, 324, 325, 327, 328, 330, 331, 360) and logically of “pulse acceleration – Pulsbeschleunigung” oder “Pulsvermehrung” (p. 324, 326, 327, 328, 329).

Yet, noticeably, Wundt did not use the term rhythm in these instances. As most of his physiologist colleagues in the 1850s and 1860s, he was still faithful to the ordinary meaning of the term in medicine.